Which Animal Was Part Of An Russian Domestication Experiment In 1959?

- Review

- Open up Access

- Published:

The silver fob domestication experiment

Evolution: Educational activity and Outreach book 11, Article number:16 (2018) Cite this article

Abstract

For the final 59 years a team of Russian geneticists led past Lyudmila Trut have been running one of the nearly important biological science experiments of the 20th, and now 21st, century. The experiment was the brainchild of Trut'southward mentor, Dmitri Belyaev, who, in 1959, began an experiment to written report the process of domestication in real time. He was especially bully on understanding the domestication of wolves to dogs, simply rather than use wolves, he used silver foxes as his subjects. Here, I provide a cursory overview of how the silver fox domestication study began and what the results to engagement have taught us (experiments continue to this 24-hour interval). I and then explain just how shut this study came to existence shut downwards for political reasons during its very first yr.

Introduction, history and findings

Today the domesticated foxes at an experimental farm most the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk, Siberia are inherently every bit calm as whatever lapdog. What's more, they look eerily dog-like. All of this is the result of what is known as the silver trick, or farm fob, domestication study. It began with a Russian geneticist named Dmitri Belyaev. In the tardily 1930s Belyaev was a pupil at the Ivanova Agricultural University in Moscow. Afterwards he graduated he fought in World War II, and subsequently landed a job at the Establish for Fur Breeding Animals in Moscow.

Both as a result of his reading of Darwin's The Variation of Animals and Plants Nether Domestication (Darwin 1868), and his interaction with domesticated animals at the Ivanova Agricultural Academy and at the Institute for Fur Breeding Animals, Belyaev knew that many domesticated species share a suite of characteristics including floppy ears, brusque, curly tails, juvenilized facial and body features, reduced stress hormone levels, mottled fur, and relatively long reproductive seasons. Today this suite of traits is known as the domestication syndrome. Belyaev constitute this perplexing. Our ancestors had domesticated species for a plethora of reasons—including transportation (due east.1000., horses), nutrient (east.g., cattle) and protection (eastward.g., dogs)—all the same regardless of what they were selected for, domesticated species, over time, begin to display traits in the domestication syndrome. Why? Belyaev hypothesized that the one thing our ancestors ever needed in a species they were domesticating was an animal that interacted prosocially with humans. We can't accept our domesticates-to-be trying to seize with teeth our heads off. And then he hypothesized that the early stages of all creature domestication events involved choosing the calmest, nigh prosocial-toward-homo animals: I will refer to this trait equally tameness, though that term is used in many dissimilar ways in the literature. Belyaev further hypothesized that all of the traits in the domestication syndrome were somehow or another, though he didn't know how or why, genetically linked to genes associated with tameness.

Belyaev set out to exam these hypotheses using a species he had worked with extensively at the Institute for Fur Breeding: the silver fox, a variant of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes). Every generation he and his squad would test hundreds of foxes, and the superlative ten% of the tamest would be selected to parent the adjacent generation. They adult a scale for scoring tameness, and how a flim-flam scored on this scale was the sole criteria for selecting foxes to parent the next generation. Belyaev could then test whether, over generations, foxes were getting tamer and tamer, and whether the traits in the domestication syndrome appeared if they selected strictly based on tameness.

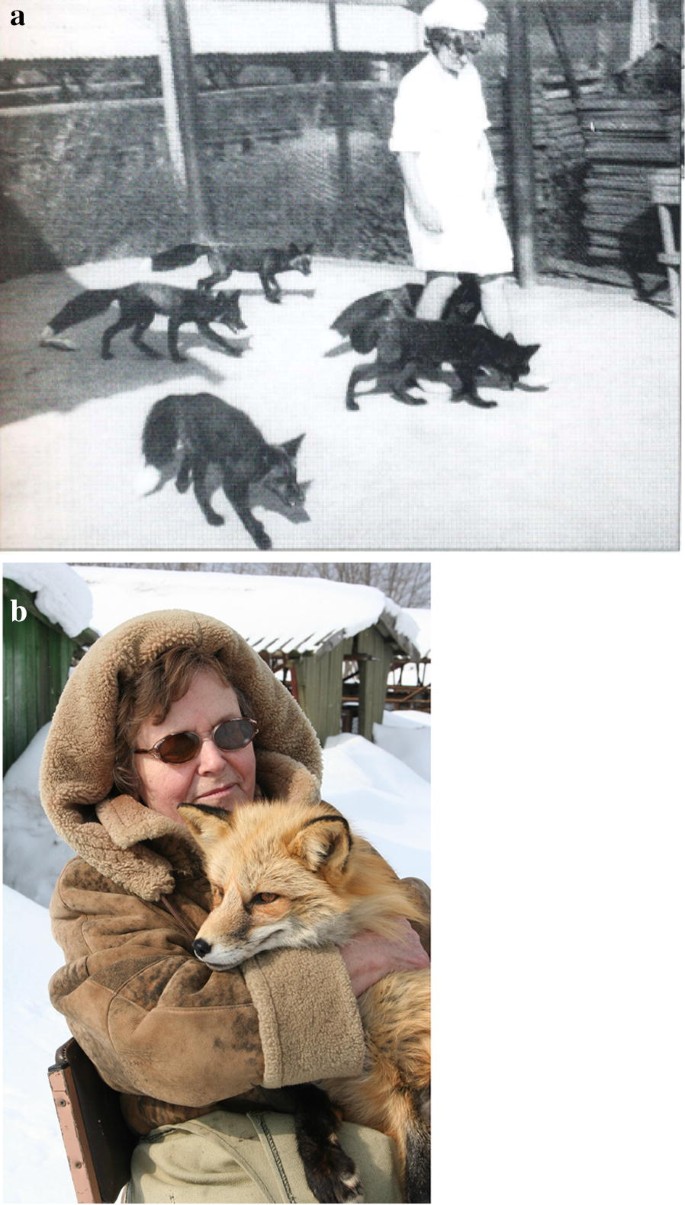

The experiment began in 1959 at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk, Siberia, shortly later on Belyaev was appointed vice manager there. Belyaev immediately recruited 25-twelvemonth-sometime Lyudmila Trut to his team (Fig. i). Trut quickly became the lead researcher on the experiment, working with Belyaev on every aspect from the applied to the conceptual. Trut turned 85 years old in Nov of 2018 and remains the pb investigator on the work to this twenty-four hours (Belyaev died in 1985).

Lyudmila Trut. a 1960 and b 2015

It is non possible here to do justice to all of the results this near vi-decade-long experiment has produced. Here I impact some of the most salient (run across Trut 1999, Trut et al. 2009 and Dugatkin and Trut 2017 for more). Starting from what amounted to a population of wild foxes, within six generations (6 years in these foxes, as they reproduce annually), selection for tameness, and tameness alone, produced a subset of foxes that licked the hand of experimenters, could exist picked up and petted, whined when humans departed, and wagged their tails when humans approached. An astonishingly fast transformation. Early on, the tamest of the foxes made upwardly a minor proportion of the foxes in the experiment: today they make upwardly the vast majority.

Belyaev was correct that selection on tameness lonely leads to the emergence of traits in the domestication syndrome. In less than a decade, some of the domesticated foxes had floppy ears and curly tails (Fig. 2). Their stress hormone levels by generation xv were near half the stress hormone (glucocorticoid) levels of wild foxes. Over generations, their adrenal gland became smaller and smaller. Serotonin levels as well increased, producing "happier" animals. Over the course of the experiment, researchers also found the domesticated foxes displayed mottled "mutt-similar" fur patterns, and they had more juvenilized facial features (shorter, rounder, more canis familiaris-like snouts) and body shapes (chunkier, rather than gracile limbs) (Fig. 3). Domesticated foxes like many domesticated animals, take longer reproductive periods than their wild progenitors. Another change associated with selection for tameness is that the domesticated foxes, unlike wild foxes, are capable of post-obit human being gaze likewise every bit dogs practise (Hare et al. 2005). In a recent paper, a "hotspot" for changes associated with domestication has been located on fox chromosome 15 (Kukekova et al. 2018). SorCS, one factor in this hotspot, is linked with synaptic plasticity, which itself is associated with retention and learning, and and so together these studies are helping u.s. better understand how the procedure of domestication has led to important changes in cognitive abilities.

Mechta (Dream), the beginning of the domesticated foxes to have floppy ears 1969

The domesticated foxes have more juvenilized facial characters, including a shorter, rounder snout, than wild foxes

Right from the start of the experiment, Belyaev hypothesized that the process of domestication was in part the consequence of changes in factor expression patterns—when genes "turn on" and "plough off" and how much protein product they produce. A contempo written report examining expression patterns at the genome level, in both domesticated foxes and a second line of foxes that has been nether long-term option for ambitious, rather than tame, behavior, suggests Belyaev was correct (Wang et al. 2018). This written report identified more than ane hundred genes in the prefrontal cortex of the brain that showed different gene expression patterns between domesticated and aggressive foxes. Some of those genes are linked to serotonin receptor pathways that modulate behavioral temperament, including tame and aggressive temperaments.

When Belyaev proposed that the domestication syndrome was linked to tame behavior, he did not take a proposed machinery, but today we are getting closer to understanding how this works. Very early on in animal evolution, what are known as neural crest cells migrate from the neural crest to a plethora of locations: glands in the endocrine arrangement, bone, fur, cartilage, the brain and other spots in a developing embryo. The neural crest jail cell hypothesis for the domestication syndrome proposes that option for tame behavior results in a reduction of the number of migrating neural crest cells, which subsequently leads to changes in fur coloration, facial structure, the forcefulness of cartilage (floppy ears, curly tails so on), hormone levels, the length of the reproductive season, and more than. This hypothesis may provide the link that Belyaev was missing when he came up with the idea for the experiment (Wilkins et al. 2014).

Discussion: a cautionary tale

The silver fox domestication written report is frequently lauded as 1 of the well-nigh of import long-term studies ever undertaken in biology. Yet in 1959, the very year it commenced, the work came within a hair's breath of existence shut down by the premier of the Soviet Union. The problem for Belyaev and Trut was that their domestication experiment, like any experiment in domestication, was an experiment in genetics. Just work in Mendelian genetics was essentially illegal at the time in the Soviet Union, because of a pseudo-scientific charlatan past the name of Trofim Lysenko (Joravsky 1979; Soyfer 1994).

In the mid-1920s, the Communist Party leadership, in an attempt to glorify the average citizen, began to promote uneducated men from the proletariat into the scientific customs. Lysenko was i of those men. The son of peasant farmers in the Ukraine, Lysenko didn't acquire how to read until he was a teenager, and his education, as information technology was, amounted to a correspondence degree from gardening school. With no training, he even so landed a middle-level task at the Gandzha Found Breeding Laboratory in Azerbaijan in 1925. Lysenko convinced a Pravda reporter, who was writing a story about the regime's glorious peasant scientists, that the yield from his pea ingather he tended was far in a higher place average, and that his technique could save a starving USSR. In the Pravda article the reporter wrote glowingly that "the barefoot professor Lysenko has followers… and the luminaries of agronomy visit… and gratefully shake his paw." Pure fiction, but the story propelled Lysenko to the national limelight, with Josef Stalin taking pride in what he read.

Over time Lysenko would claim to have done experiments creating grain crops, including wheat and barley, that produced high yields during cold periods of the yr, if their seeds had been kept in freezing h2o for long stretches before planting. What's more than, Lysenko claimed offspring of these plants would also produce higher yields, downward through the generations. This method, he said, could quickly double the yield of farmlands in the Soviet Union in simply a few years. In truth, Lysenko never undertook any legitimate experiments on increased crop yield. Whatever "data" he claimed to have produced he simply fabricated.

Soon Stalin was his ally, and Lysenko began a crusade to ignominy work in Mendelian genetics because proof of the genetic theory of evolution would probable betrayal him every bit a fraud. He denounced geneticists, both overseas and in the Soviet Union, every bit subversives. His star was rising and at a conference held at the Kremlin in 1935, after Lysenko finished a spoken language in which he branded Western geneticists every bit "saboteurs," Stalin stood up to yell, "Bravo, Comrade Lysenko, bravo."

Lysenko was placed in accuse of all policy regarding the biological sciences in July 1948. The side by side month, at a meeting of the All-Wedlock Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences, he presented a talk that today is regarded as the well-nigh disingenuous, dangerous voice communication in the history of Soviet scientific discipline. In this speech communication, "The State of affairs in the Science of Biology," Lysenko damned "modern reactionary genetics," by which he meant Mendelian genetics. At the end of his ranting, the audition cheered wildly. Geneticists present were forced to stand up and abnegate their scientific knowledge and practices. If they refused, they were thrown out of the Communist Party. In the aftermath of that awful speech thousands of geneticists were fired from their jobs. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, were jailed, and a few were murdered by Lysenko's henchmen.

Belyaev could non sit by idly. Afterward reading of Lysenko's speech in the newspaper, he was furious. His married woman, Svetlana, remembers it well: "Dmitri was walking toward me with tough sorrowful eyes, restlessly bending and angle the newspaper in his hands." Some other colleague recalls running into him that day and how Belyaev had fumed that Lysenko was "a scientific bandit" (Dugatkin and Trut 2017). Ignoring the personal risk, Belyaev began speaking out about the dangers of Lysenkoism to all scientists, whether friend or foe.

The case of Nikolai Vavilov, ane of Belyaev'due south intellectual idols, illustrates just how dangerous it was to speak out confronting Lysenko (Medvedev 1969; Pringle 2008; Soyfer 1994). Vavilov studied constitute domestication and was also i of the world's leading botanical explorers, travelling to 60-4 countries collecting seeds. In his lifetime alone, three terrible famines in Russia killed millions of people and Vavilov had dedicated his life to finding ways to propagate crops for his country. His inquiry programme centered on finding crop varieties that were less susceptible to disease.

Vavilov's collecting trips are the stuff of fable. On one of 3 expeditions, he was arrested at the Iran-Russia border and accused of beingness a spy, merely considering he had a few German botany books with him. On another trip, this 1 to the edge of Afghanistan, he fell equally he was stepping between two train cars, and was left dangling by his elbows as the train roared along. On yet a unlike a trip to Syria he contracted malaria and typhus.

Vavilov collected more live establish specimens than whatever man or woman in history, and he set hundreds of field stations for others to keep his work.

Vavilov had really befriended the young Lysenko in the 1920s, before it became clear that Lysenko was a malevolent adventurer. Over time, Vavilov became suspicious of Lysenko's results, and in a series of experiments trying to replicate what Lysenko said he had discovered, Vavilov proved to himself, and others that were willing to listen (though not many were), that Lysenko was a fraud. He then became Lysenko's nigh fearless opponent. In retaliation, Stalin forbade Vavilov from any more than travels abroad and he was denounced in the government newspaper, Pravda. Lysenko warned Vavilov that "when such erroneous information were swept away… those who failed to understand the implications" would also be "swept away." Vavilov was undeterred, and at a coming together of the All-Marriage Institute of Plant Convenance declared, "We shall go into the pyre, we shall burn down, simply we shall not retreat from our convictions."

In 1940, Vavilov was kidnapped upward by four men wearing dark suits and thrown into the KGB's dreaded Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. Next he was shipped off to an even more than remote prison. There, over the form of iii years, the man who had collected 250,000 domesticated plant samples to solve the puzzle of famine in his homeland was slowly starved to decease.

Lysenko's power had its ebbs and flows. In 1959, as the fob domestication experiment was only beginning, Lysenko was getting frustrated that his concord on Soviet biology was loosening. Something needed to be washed. And The Establish of Cytology and Genetics, where the fox domestication experiment had merely begun, where Belyaev was vice director, and where they had the brazenness to put "Genetics" in the title of the found, seemed a good identify to attack.

The Institute of Cytology and Genetics was part of a new giant scientific city called Akademgorodok. Long before this urban center was built, Russian author Saying Gorky had written of a fictional "town of science… a series of temples in which every scientist is a priest… where scientists every twenty-four hour period fearlessly probe deeply into the baffling mysteries surrounding our planet." Here Gorky envisioned "…foundries and workshops where people forge verbal knowledge, facet the unabridged experience of the globe, transforming it into hypotheses, into instruments for the further quest of the truth." Akademgorodok was what Gorky had in mind. Information technology was home to thousands of scientists housed at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, the Institute of Mathematics, the Institute of Nuclear Physics, the Institute of Hydrodynamics, and a half-dozen other institutes.

In Jan 1959, a Lysenko-created committee from Moscow was sent to Akademgorodok. This committee had been authorized to decide just what sort of work was being done at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, and Belyaev, Trut and their colleagues understood the gravity of the situation. "Committee members were, Trut said, "snooping in the laboratories," and rumors were spreading that the committee was unhappy. When the committee met with Mikhail Lavrentyev, chief of all the institutes at Akademgorodok, they told him that "the direction of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics is methodologically wrong" (Dugatkin and Trut 2017). Ominous words from a Lysenkoist grouping.

Nikita Khrushchev, premier of the USSR, learned of the committee'south report virtually Akademgorodok. Khrushchev was a supporter of Lysenko, and he decided to run into for himself what was happening. In September 1959, while returning from a visit to Mao Tse-Tung in China, he stopped off in Novosibirsk and went to Akademgordok.

The staff of all the science institutes at Akademgorodok gathered for this visit, and Trut remembers that the premier "walked past the assembled staff very fast, not paying whatever attention to them" as he proceeded to a meeting with administrators. "Khrushchev" Trut recalls was, "very discontented, with the intention to get everyone in problem because of the geneticists." What Khrushchev and Akademgorodok administrators said that day was not recorded, just accounts from the fourth dimension make articulate that the premier intended to shut down the Institute of Cytology and Genetics that day, and with it the nascent silver trick domestication experiment.

Fortunately for science, Khrushchev's daughter, Rada, was with him in Akademgorodok. Rada, a well-respected journalist, had trained as a biologist, and understood very well that Lysenko was a fraud. She somehow managed to convince her father to let the Institute of Cytology and Genetics remain open. In an ironic twist, because Khrushchev felt he had to do something to show his discontent, the day after his visit, he fired the head of the Establish of Cytology and Genetics. Deputy Manager Belyaev was now in charge of the plant.

If Rada Khrushchev had not taken a stand for scientific discipline that 24-hour interval the fox domestication study would probable have ended before information technology even got off the basis. Merely, it survived and thrived and continues to shed new light on the process of domestication.

References

-

Darwin C. The variation of animals and plants under domestication. London: J. Murray; 1868.

-

Dugatkin LA, Trut LN. How to tame a fox (and build a dog). Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2017.

-

Hare B, Plyusnina I, Ignacio N, Schepina O, Stepika A, Wrangham R, Trut L. Social cognitive development in captive foxes is a correlated past-product of experimental domestication. Curr Biol. 2005;15:226–30.

-

Joravsky D. The Lysenko affair. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979.

-

Kukekova AV, Johnson JL, Xiang X, Feng S, Liu S, Rando HM, Kharlamova AV, Herbeck Y, Serdyukova NA, Xiong Z, Beklemischeva V, Koepfli Chiliad-P, Gulevich RG, Vladimirova AV, Hekman JP, Perelman PL, Graphodatsky AS, Obrien SJ, Wang X, Clark AG, Acland GM, Trut LN, Zhang 1000. Red fox genome assembly identifies genomic regions associated with tame and aggressive behaviours. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0611-6.

-

Medvedev Z. The rise and fall of T.D. Lysenko: Columbia University Press; 1969.

-

Pringle P. The murder of Nikolai Vavilov. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2008.

-

Soyfer VN. Lysenko and the tragedy of Soviet science. Newark: Rutgers University Press; 1994.

-

Trut LN. Early canid domestication: the farm-fob experiment. Am Sci. 1999;87:160–9.

-

Trut LN, Oskina I, Kharlamova A. Animal evolution during domestication: the domesticated fox as a model. BioEssays. 2009;31:349–60.

-

Wang X, Pipes L, Trut LN, Herbeck Y, Vladimirova AV, Gulevich RG, Kharlamova AV, Johnson JL, Acland GM, Kukekova AV, Clark AG. Genomic responses to pick for tame/aggressive behaviors in the silver play a trick on (Vulpes vulpes). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:10398–403.

-

Wilkins AS, Wrangham R, Fitch TW. The "domestication syndrome" in mammals: a unified explanation based on neural crest cell behavior and genetics. Genetics. 2014;197:795–808.

Authors' contributions

The author read and canonical the last manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I thank Lyudmila Trut for working with me on our book, How to Tame a Fox and Build a Dog (University of Chicago Press, 2017). Nikolai and Michael Belyaev provided much in the manner of aid, every bit did Aaron Dugatkin. I thank Dana Dugatkin for proofreading this paper.

Availability of data and materials

No primary data was included in this review.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Publisher's Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Writer information

Authors and Affiliations

Respective author

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and betoken if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dugatkin, L.A. The silver fox domestication experiment. Evo Edu Outreach 11, 16 (2018). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12052-018-0090-x

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-018-0090-x

Keywords

- Domestication

- Development

- Silvery foxes

Source: https://evolution-outreach.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12052-018-0090-x

Posted by: millerpithenclacke.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Animal Was Part Of An Russian Domestication Experiment In 1959?"

Post a Comment